原文地址:

The usual test for chaos is calculation of the largest Lyapunov exponent. A positive largest Lyapunov exponent indicates chaos. When one has access to the equations generating the chaos, this is relatively easy to do. When one only has access to an experimental data record, such a calculation is difficult to impossible, and that case will not be considered here. The general idea is to follow two nearby orbits and to calculate their average logarithmic rate of separation. Whenever they get too far apart, one of the orbits has to be moved back to the vicinity of the other along the line of separation. A conservative procedure is to do this at each iteration. The complete procedure is as follows:

1. Start with any initial condition in the basin of attraction.

Even better would be to start with a point known to be on the attractor, in which case step 2 can be omitted.

2. Iterate until the orbit is on the attractor.This requires some judgement or prior knowledge of the system under study. For most systems, it is safe just to iterate a few hundred times and assume that is sufficient. It usually will be, and in any case, the error incurred by being slightly off the attractor is usually not large unless you happen to be very close to a bifurcation point.

3. Select (almost any) nearby point (separated by d0).An appropriate choice of d0 is one that is on the order of the square root of the precision of the floating point numbers that are being used. For example, in (8-byte) double-precision (minimum recommended for such calculations), variables have a 52-bit mantissa, and the precision is thus 2-52= 2.22 x 10-16. Therefore a value of d0= 10-8 will usually suffice.

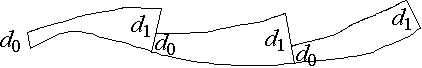

4. Advance both orbits one iteration and calculate the new separation d1.

The separation is calculated from the sum of the squares of the differences in each variable. So for a 2-dimensional system with variables x and y, the separation would be d = [(xa - xb)2 + (ya - yb)2]1/2, where the subscripts (a and b) denote the two orbits respectively.

5. Evaluate log |d1/d0| in any convenient base.By convention, the natural logarithm (base-e) is usually used, but for maps, the Lyapunov exponent is often quoted in bits per iteration, in which case you would need to use base-2. (Note that log2x = 1.4427 logex). You may get run-time errors when evaluating the logarithm if d1 becomes so small as to be indistinguishable from zero. In such a case, try using a larger value of d0. If this doesn't suffice, you may have to ignore values where this happens, but in doing so, your calculation of the Lyapunov exponent will be somewhat in error.

6. Readjust one orbit so its separation is d0 and is in the same direction as d1.This is probably the most difficult and error-prone step. As an example (in 2-dimensions), suppose orbit b is the one to be adjusted and its value after one iteration is (xb1, yb1). It would then be reinitialized to xb0 = xa1 + d0(xb1 - xa1) / d1 and yb0 = ya1 + d0(yb1 - ya1) / d1.

|

7. Repeat steps 4-6 many times and calculate the average of step 5.

You might wish to discard the first few values you obtain to be sure the orbits have oriented themselves along the direction of maximum expansion. It is also a good idea to calculate a running average as an indication of whether the values have settled down to a unique number and to get an indication of the reliability of the calculation. Sometimes, the result converges rather slowly, but a few thousand iterates of a map usually suffices to obtain an estimate accurate to about two significant digits. It is a good idea to verify that your result is independent of initial conditions, the value of d0, and the number of iterations included in the average. You may also want to test for unbounded orbits, since you will probably get numerical errors and the Lyapunov exponent will not be meaningful in such a case.